Juneau is the capital of Alaska, the third largest city in Alaska with a population of just over 30K. The Borough of Juneau is also the third largest municipality by area in the USA. The population of Juneau city occupies a narrow tidal strip along the east side of the Gastineau Channel. It is backed by steep forested mountains over 1km high, on top of which sits the southern extent of the Juneau Ice Field.

From Juneau, we chose a float plane excursion. Taking off from the Juneau waterfront, four 10-passenger DeHavilland Otter turboprops took the entire group up over the glaciers that terminate along Taku Inlet: Norris, Taku, Hole-in-Wall, and Twin. We would land on Taku Inlet next to a small lodge with a storied history, where we would have brunch and a two hour visit before returning.

The Taku glacier is the only advancing glacier connected to the Juneau Ice Field. It is also one of the largest, about 1.5km thick at its deepest. Its advance has almost filled the Taku inlet with sediment, so calving is no longer occurring. But it is still technically a tidewater glacier.

Slightly east of Taku glacier, our pilot flew over the twin glaciers known as West and East Glacier, which terminate in a small lake adjacent to Taku Inlet.

Directly across the inlet from the lodge is an arm of the Taku glacier called Hole-in-the Wall glacier.

We had brunch at the lodge, a fresh king salmon barbecue served with baked beans, cole slaw, venison sausage, apple compote, and biscuits. A selling point for this excursion is the near certain appearance of at least one black bear after the fish bake. On cue, a large bear came to lick the BBQ pit clean after the cooking was done. It interested me that a totally habituated bear can still be accommodated by human activity without substantial risk to either; apparently these are smart bears associating with savvy people.

The Lodge was owned by adventurer Mary Joyce during the 1930s. She bred sled dogs and in December of 1935 hitched her five best dogs to a sled and, accompanied by native guides on each leg, drove 1000 miles from Taku to Fairbanks, a feat that defied her many naysayers. She later owned and ran the Lucky Lady bar, still operating in Juneau (street scene below).

We flew back directly to Juneau after brunch, first getting a glimpse of glaciers on the south side of Taku Inlet, not connected to the Juneau Ice Field. Our flight ended with views of Juneau harbor and our ship.

I did a short walk-about in Juneau before returning to the ship.

The ship left Juneau around 2PM and headed for the Endicott Arm, a fjord south of Juneau that ends at the Dawes tidewater glacier. We were also supposed to see the Sawyer glacier on the adjacent Tracy Arm, but apparently a late sailing time, due to some excursion not returning on time, cost us the opportunity.

The upper reaches of Endicott Arm are a brilliant cyan color in reflected sunlight, possibly due to the light-density glacial melt water overlaying the more dense salt water beneath. Various sizes of blue glacial ice decorate the still surface, remnants of glacial calving.

The inlet is lined with steep rock cliffs, many of which display unusual scouring marks from a prior glacial advance. At one point, the glacial melt merges with another arm that is a brownish color, reflecting the high silt content deposited by alpine rivers draining from above.

The size of Dawes Glacier is hard to fathom from our distance, but the double-deck excursion boat next to it gives a sense of scale.

After the glacier visit, the ship sailed overnight to the northern terminus of our trip, Skagway, itself the terminus of the White Pass and Yukon Railway. The town and the railway have a symbiotic relationship, for it appears neither would be likely to continue existence without the other.

There was little time to visit Skagway itself, which seems little more than an outpost. Our guides provided some local flavor. The store gets provisions on Tuesday, so eggs and milk are hard to come by on the weekends. Accommodations in town are expensive, so seasonal help become 'tarpologists', erecting living quarters out of pieces of canvas. A rogue bear had become a nuisance in town recently, but the imminent start of hunting season would soon correct that. Skagway life seems to possess an elemental quality that would not appeal to many nowadays.

Debby and I both headed out on the train the next morning. Debby rode the train up to the Canadian border and back, soaking up the alpine scenery along the route.

My group left an hour earlier and went only part way.

About 15km up, there is a view for a few seconds of the tall, many-tiered Bridal Veil Falls; the lower sections are visible here.

The train stopped and dropped us next to a trail head from which 14 intrepid hikers and three guides, armed only with bear spray, climbed up to Laughton Glacier and back, about a 6 hour trek. When reaching the glacial stream descending from Laughton, we experienced the full view of where we were headed.

After the trail left the forest, we had to ford the stream.

We climbed up the medial moraine on the long tongue of the glacier. Here the ice is thinly disguised by a coating of fractured granite, with the icy substrate occasionally showing itself.

Beyond the lateral moraine, the alpine ground is beginning to show fall coloring.

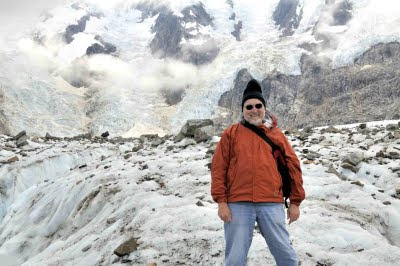

The group spread out on a final scramble up to the steep glaciated slopes.

A bear (brown?) greeted our return to the railway tracks, moseying around less than .5km away, but apparently oblivious to our presence. We waited for three trains to pass before one stopped for us, making us an hour late back to the ship.

There had been a one hour talk about glaciers on the ship before we had arrived at Juneau. Combined with the field trips, we came away from our cruise with an appreciation of the beauty of glaciers, and their power to rework the topology of the land masses they pass over. But the glaciers were just one aspect of the immense wilderness that is Alaska. Perhaps a humbling visit to Alaska would be a good tonic for any who view themselves as masters of their world.

We flew back directly to Juneau after brunch, first getting a glimpse of glaciers on the south side of Taku Inlet, not connected to the Juneau Ice Field. Our flight ended with views of Juneau harbor and our ship.

I did a short walk-about in Juneau before returning to the ship.

The ship left Juneau around 2PM and headed for the Endicott Arm, a fjord south of Juneau that ends at the Dawes tidewater glacier. We were also supposed to see the Sawyer glacier on the adjacent Tracy Arm, but apparently a late sailing time, due to some excursion not returning on time, cost us the opportunity.

The upper reaches of Endicott Arm are a brilliant cyan color in reflected sunlight, possibly due to the light-density glacial melt water overlaying the more dense salt water beneath. Various sizes of blue glacial ice decorate the still surface, remnants of glacial calving.

The inlet is lined with steep rock cliffs, many of which display unusual scouring marks from a prior glacial advance. At one point, the glacial melt merges with another arm that is a brownish color, reflecting the high silt content deposited by alpine rivers draining from above.

The size of Dawes Glacier is hard to fathom from our distance, but the double-deck excursion boat next to it gives a sense of scale.

After the glacier visit, the ship sailed overnight to the northern terminus of our trip, Skagway, itself the terminus of the White Pass and Yukon Railway. The town and the railway have a symbiotic relationship, for it appears neither would be likely to continue existence without the other.

There was little time to visit Skagway itself, which seems little more than an outpost. Our guides provided some local flavor. The store gets provisions on Tuesday, so eggs and milk are hard to come by on the weekends. Accommodations in town are expensive, so seasonal help become 'tarpologists', erecting living quarters out of pieces of canvas. A rogue bear had become a nuisance in town recently, but the imminent start of hunting season would soon correct that. Skagway life seems to possess an elemental quality that would not appeal to many nowadays.

Debby and I both headed out on the train the next morning. Debby rode the train up to the Canadian border and back, soaking up the alpine scenery along the route.

My group left an hour earlier and went only part way.

About 15km up, there is a view for a few seconds of the tall, many-tiered Bridal Veil Falls; the lower sections are visible here.

The train stopped and dropped us next to a trail head from which 14 intrepid hikers and three guides, armed only with bear spray, climbed up to Laughton Glacier and back, about a 6 hour trek. When reaching the glacial stream descending from Laughton, we experienced the full view of where we were headed.

After the trail left the forest, we had to ford the stream.

We climbed up the medial moraine on the long tongue of the glacier. Here the ice is thinly disguised by a coating of fractured granite, with the icy substrate occasionally showing itself.

Beyond the lateral moraine, the alpine ground is beginning to show fall coloring.

The group spread out on a final scramble up to the steep glaciated slopes.

A bear (brown?) greeted our return to the railway tracks, moseying around less than .5km away, but apparently oblivious to our presence. We waited for three trains to pass before one stopped for us, making us an hour late back to the ship.

There had been a one hour talk about glaciers on the ship before we had arrived at Juneau. Combined with the field trips, we came away from our cruise with an appreciation of the beauty of glaciers, and their power to rework the topology of the land masses they pass over. But the glaciers were just one aspect of the immense wilderness that is Alaska. Perhaps a humbling visit to Alaska would be a good tonic for any who view themselves as masters of their world.

No comments:

Post a Comment